Nearly four generations of viewers – and their parents and teachers – have enjoyed the catchy songs and lively images of the animated series Schoolhouse Rock. Inserted between the requisite Saturday morning cartoons on ABC, the three-minute shorts taught billions of kids their multiplication tables, parts of speech, and American history. Little known however, is the jazz pedigree of the groundbreaking series.

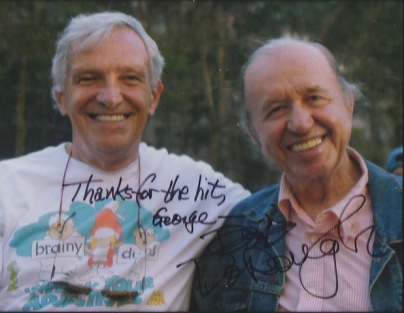

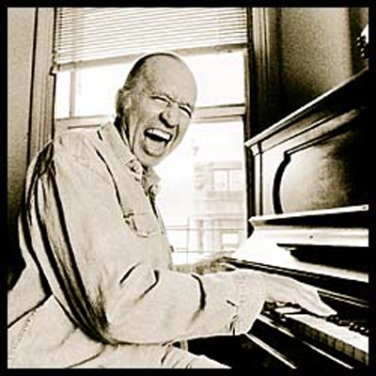

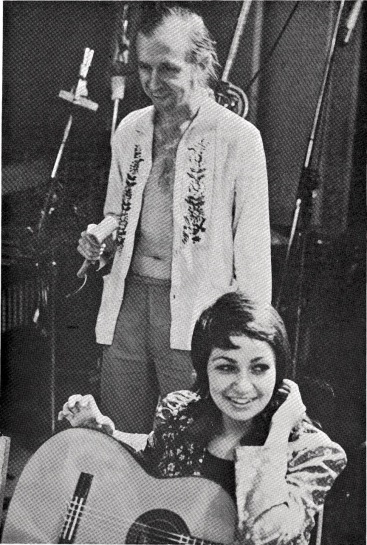

The title, “Schoolhouse Rock” belies the fact that most of the songs in all six series were written and/or co-written by uber-hip jazz pianist and vocalist Bob Dorough. George Newall, a composer and pianist who at the time of the series’ creation was co-creative director at McCaffrey & McCall, an advertising firm in New York, also composed many of the songs throughout Schoolhouse Rock’s nearly 30-year run. In addition, a small but mighty firmament of jazz luminaries had a significant impact on the series in its infancy. Lynn Ahrens, who was a secretary at McCaffrey & McCall when Schoolhouse Rock was in its first series, is responsible for the fact that generations of schoolkids now know the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution by heart, thanks to her songwriting and vocal skills. She wrote 20 of the songs, among them three of the most memorable: “Interjections,” and “The Tale of Mr. Morton” for “Grammar Rock,” and “Interplanet Janet” for “Science Rock.”

The original series which included “Multiplication Rock,” “Grammar Rock,” “Science Rock,” and “America Rock,” originally ran from 1973 to 1985. A subsequent series, “Money Rock,” as well as additions to “Grammar Rock,” were created in the early 1990s. “Earth Rock” was produced in 2009 for video release.

The idea for Schoolhouse Rock came from David McCall, president of McCaffrey & McCall. He was concerned that his son, who could easily memorize the lyrics to any rock and roll tune, had difficulty remembering his multiplication tables, and enlisted the help of Newall to find a way to reinforce learning through music. The results have become a cultural phenomenon that has been widely admired, imitated, and parodied. A musical titled “Schoolhouse Rock Live” was penned in the 1990s by a couple of Northwestern University students who fondly remembered the series and wanted to create an homage. Their show – which have received the blessings of Dorough and Newall – has made it to off-Broadway, with productions around the world.

Bass player Ben Tucker introduced a number of artists to the project and served as its musical contractor. Tucker wrote the instrumental version of “Comin’ Home Baby,” which became a huge hit for Mel Torme, who sang lyrics by none other than Dorough. Some of the most memorable Schoolhouse Rock performances were given by trumpeter and vocalist Jack Sheldon, who sang throughout the series, including “Conjunction Junction” and one of the series’ all-time favorites, “I’m Just a Bill.” Grady Tate, who started out in the early 1960s as a drummer for Quincy Jones, delivered “I Got Six,” and “Naughty Number Nine” for “Multiplication Rock.” Blossom Dearie’s dulcet tones lent themselves to “Figure Eight,” “Mother Necessity,” and “Unpack Your Adjectives,” which was written by Newall and covered by vocalist Sarah Gazarek on her 2012 tribute to Dearie titled, “Blossom and Bee.” Dave Frishberg, known for acerbic ditties like “Peel Me a Grape,” “Do You Miss New York?” and “Van Lingle Mungo,” sang “Walkin’ on Wall Street” and “$7.50 Once a Week,” which he co-wrote with Mark Chapalonis for the “Money Rock” series, and “I’m Just a Bill.”

At nearly 94, Dorough is still swinging. He performed this summer at Delaware Water Gap in Pennsylvania and is slated for another concert there in September, vocalist Nancy Reed, another Schoolhouse Rock alumna. He also delivered a TEDx Talk in 2016 on “Schoolhouse Rock Explained” as part of a series on education. His estimable career in jazz – and other genres – has established him as a singer/songwriter, composer, producer, and arranger. Partnering with composer Stuart Scharf, Dorough arranged and produced two albums for the 1960s folk-pop band Spanky and Our Gang. His compositions, “I’m Hip” (with Dave Frishberg); “Devil May Care” (with Terrell Kirk); and “Nothing Like You,” which he performed on Miles Davis’s 1966 album “Sorcerer,” have become part of the jazz canon.

In 1978, Ahrens, who started out at McCaffrey & McCall as a secretary but soon after became a copywriter and later, a senior vice president, went off to freelance as a full-time songwriter, writing for television and doing advertising jingles. Among them, “Bounty-the-Quicker-Picker-Upper” and “What Would You Do for a Klondike Bar?” burned themselves into the consumer subconscious in the 1980s-90s, thanks to Ahrens’ signature way with words. In 1983, she began writing for theater and went on to win countless accolades, including the Tony Award and Oscar nominations for such works as “Once on This Island,” “Ragtime,” and “Anastasia.” In 2014, she and longtime collaborator Stephen Flaherty received the Oscar Hammerstein Award for Lifetime Achievement, and in 2015 they were inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame.

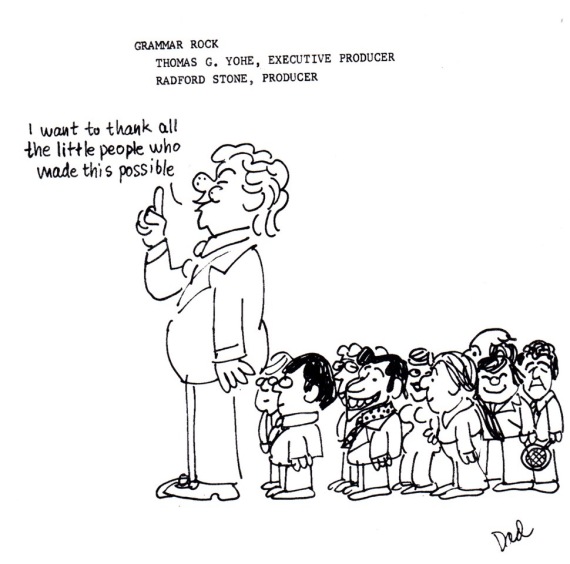

Newall, who had created the famed “Hai Karate” after shave campaign in the 1960s, left McCaffrey & McCall in 1978, along with co-creative director Tom Yohe, the artist behind the iconic drawings and animation of Schoolhouse Rock. They went on to create more children’s television features and garnered numerous awards for their work including Emmy nominations for spots on nutrition for ABC, and “The Metric Marvels” and “When You Turn Off Your Set, Turn On a Book” for NBC. Yohe and Newall were also honored with an Action for Children’s Television (ACT) Award for their work on “Drawing Power,” an Emmy-winning Saturday morning series they created for NBC in 1987. The ACT citation commended the pair for proving that “cartoons could be non-racist, non-sexist, informative, and funny.” Newall, who is an accomplished jazz pianist and composer, has recorded several albums, including “Return to Jazz Standards,” with his wife Lisa Maxwell, who is a jazz vocalist.

Nearly 45 years after Schoolhouse Rock was created, Ahrens, Dorough, and Newall shared their experiences on combining Madison Avenue savvy with the Three R’s; the ways that music has affected and enhanced their career choices, and the intergenerational and global appreciation of the innovative teaching methods – and sheer “heart” – that characterize Schoolhouse Rock.

How did Schoolhouse Rock get its start, musically and visually?

Bob Dorough: I actually had done one or two advertising jobs for McCaffrey & McCall and got to know George that way. Being a jazz fan, he went to the Hickory House where my friend and writing partner Ben Tucker was playing the bass. One night he said to Ben, “My boss is looking for someone to put the multiplication tables to music.”

Well, I’d written a lot of songs. I called them “pop-eyed songs,” where I got the words or the idea from ordinary sources. Ben said, right away, “My pal Bob Dorough can do it, he can set anything to music.”

I knew it was a great opportunity for me and figured the first song had to be good. I just picked three out of the series of numbers and wrote, ‘Three is a Magic Number.’ I was aware of the New Math, so I did a little research and attacked the problem from the back end in that particular song, [talking] about all the properties and the trinities concerning three before I began to deal with the multiplication part. The song is already a minute and 20 seconds old before I say, “Count by three and multiply backwards from 3 X 10.” It was really off the wall and I thought, if they are really looking for something out of the ordinary, I’m going to give it to them with the first song, win or lose.

And of course, I won. They were crazy about the song, and suddenly, I was a paid songwriter. It took me about three years to do “Multiplication Rock” from that moment. We weren’t in a hurry – we probably started in 1970 or 1971. I wrote the numbers one at a time and I’d bring them in.

Eventually, they wanted to record. Ben Tucker was the bassist and I played the keyboards and did the singing because we didn’t really know what we were doing yet. But we wound up making a whole album called, “Multiplication Rock,” and it was actually put out on Capitol Records. This is all before the idea of [Schoolhouse Rock on] television came into our lives.

Lynn Ahrens: When I was little, my mom read out loud to me, doing all the voices of the characters in my books and making up tunes to the rhymes. I started writing little songs at about the age of 4, and have never stopped. I think that early “ear-training” gave me a love of words and music. When I was applying to colleges, someone suggested Syracuse University. They said the Newhouse School of Journalism was a terrific place for anyone who had a way with words. I ended up going there—a dual major in English and Journalism—and thought I’d probably end up working in the world of magazines.

I knew I wanted to live in New York City. When I graduated, I moved to New York without a cent, and would have taken the first job offered. That turned out to be a job as a secretary at McCaffrey & McCall, and my journalism degree actually served me pretty well. It was a wonderful place to work—there was always laughter in the halls. To a kid fresh out of college, it felt like an ongoing party.

I used to bring my guitar to work so I could write songs on my lunch hour. One day, George Newall passed my desk, and said, “I hear you write songs. Would you like to write one for Schoolhouse Rock?” Lo and behold, one song led to another and I became one of their regular songwriters. I was simultaneously promoted to the job of copywriter and so did both copywriting and songwriting for about seven years.

George Newall: I ran the copy department and my friend Tom Yohe ran the art department. He heard “Three is a Magic Number” and started doodling the characters.

Our biggest client at the time was ABC Television. We did all their tune-in advertising and all of their corporate advertising as well. The guy who ran that was named Rad Stone. He just happened to drop into the office one day when Tom was listening to the music and doodling character possibilities and he said, “Hey, do you think you could make a storyboard out of that?” ABC is looking for short form educational programming.

Tom said he could, so he did a storyboard and we set up a meeting. The head of children’s programming at the time was a young guy named Mike Eisner who later became the CEO of Disney. ABC was doing an anthology show to be produced by Chuck Jones – the celebrated father of animated cartoons like Bugs Bunny and the Roadrunner. They started the tape recorder and Tom took them through the board. Eisner turned to Jones and asked, ‘What do you think?’ Jones said, “Buy it, as long as he draws it,” pointing to Tom. In a world where people make hundreds of presentations before selling an idea, we had one meeting and we were on network television.

George, how did your advertising knowledge and skills help to present the ideas and instruction behind Schoolhouse Rock?

We were on five times every Saturday morning and three times every Sunday morning. We were actually sponsored and it used to be listed in the TV Guide as if it were a real program. Writing a song that people remember is very similar to doing advertising – it’s all concept-based. The strongest songs are the ones that have those really simple concepts that are easy to understand.

The two examples I can give you are “Conjunction Junction,” which Bob wrote from an idea I had about a railroad switching yard to hook up words and phrases. And I wrote a song called “Unpack Your Adjectives.” A kid comes back from vacation and people ask her about it and she “unpacks” [descriptive words]: it was raining, it was snowing, it was hot. If you have a simple, easy to understand concept, that is what will sell a product. In this case, it sold the multiplication tables.

Were there many changes to the songs when Schoolhouse Rock became a television series?

Dorough: When you write songs out of the clear blue sky, you don’t time them, the song takes its own form. They were of different lengths, that was the problem. The first thing that happened that determined the program size was that every song had to be three minutes, no more, no less. I had written jingles where they said it had to be 30 seconds, I was used to dealing with time. I had to retrofit quite a few of the songs to fulfill that three-minute size.

One of the most interesting things was that I had a song about multiplying by two, “Elementary, my dear… two times two is four.” Tom Yohe, who was the animation genius, said, ‘I’m thinking of making it about Noah’s Ark, two by two, two of every kind of animal.” When he said that, I said, “Oh, it’s a little short.” So, I recorded the verse with just piano, not a band, and we tacked it on in the beginning – a little intro about Noah:

(sings)

Forty days and forty nights

Didn’t it rain, children

Not a speck of land in sight

Didn’t it, didn’t it rain

But Noah built his ark so tight

That he sailed on, children

And when at last the waters receded

And the dove brought back the olive tree leaf

They landed that ship near Mount Ararat

And one of the kids grabbed Noah’s robe and said,

“Hey, Dad – how many animals are on this old ark anyhow?”

Then the song started. That would never had happened had there not been the [requirement] to make every song three minutes.

Was there any educational research done to help in the creation of the songs and the series?

Newall: David McCall was on the board of the Bank Street School of Education. When the long-playing album of the songs was released, a couple of the multiplication songs were given to Bank Street and they got them into public schools, inner city schools, and country schools to test, and they did very well.

At one point, Bob wrote a song called “Little Twelvetoes.” It was about the 12 multiplication tables, and it was very complex. Eisner said, ‘Wait a minute – no kid is going to understand this.’ So, we said, ‘Call the Bank Street School.’ He got on the phone and our Bank Street consultant Dorothy Bloomberg said ‘Just because you don’t understand it doesn’t mean kids won’t understand it.’ (laughs)

Dorough: At the time, my daughter was eight-years-old. I always played the songs here at home before I played them for McCall and the gang. I didn’t go too often into the schools, but my wife and daughter were always there, listening to [the songs] and commenting. They were a good sounding board. And of course, as a songwriter already I’d written a number of songs and had my own built-in criteria.

Schoolhouse Rock reflects the educational trends and priorities of the times that it was created in, starting with the 3 R’s and evolving to more political, economic, and environmental issues. How did the Schoolhouse Rock creative team capture this evolution through music and visuals?

Ahrens: The series certainly did evolve. I think that’s the strength of Schoolhouse Rock —that it can handle whatever seems most important for our times, and do it with fun and grace. In the early days, we would be told to write pretty much anything we wanted to, as long as it fit under the category of “Grammar” or “America.” The last four songs I wrote all had to do with the environment. In this last go-round, the topics were assigned—i.e. “The Rain Forest,” “Recycling,” and so forth. It was certainly more freewheeling in the old days.

I think that inherent in a lot of the pieces we all wrote is a liberal mindset and a sense of inclusion. Look at “The Great American Melting Pot,” “The Preamble,” “Fireworks,” “Sufferin’ Till Suffrage,” and many more. I don’t think I ever consciously set out to put forth an agenda. It was mainly about teaching a little something in an entertaining way, although over the years I think we’ve all become more political. When Obama was running for election, I did write new lyrics to one of my songs (“Nouns”) and a friend cut together some of the old footage, to help get out the vote. You can find it on YouTube if you Google “Schoolhouse Rock the Vote.”

What is it like when you realize the impact that Schoolhouse Rock has had, not just on elementary education, but on our collective consciousness in the United States and around the world?

Newall: It was a seat-of-the-pants things and people liked it. We had no idea that it was developing a cult-like following. We had a couple of things going for us. We were an advertising agency, not a film production or television production house, so we always had a very independent feeling about what we created because it wasn’t what we were doing for a living. We were making very good money in advertising already. Most TV producers are too timid to take chances because they’re obsessed over whether their shows get picked up again the next year.

And a lot of the work – not the recording sessions, but the drawing and designing of the cartoons was done on the kitchen table at home after work. I don’t remember ever seeing Tom work on a storyboard in the office, he always did this at home or on the way to work on the train. We had “day jobs,” so that gave us a certain amount of independence.

Dorough: Once it was on television, I was dumbfounded. I hadn’t watched cartoons at all – I’ve been watching cartoons myself every Saturday since. My daughter didn’t watch television that often, but we tuned on every Saturday and heard my voice and I thought, “Wow, I wonder if anyone is seeing this.”

I volunteered in Manhattan to do some school assemblies around Christmastime after Schoolhouse Rock had been on television for a year. I put on a big act and said, “I’m from ABC, and we have a show for you.” They’d say, “We don’t have any money.” And I’d say, “This is a free show, compliments of Schoolhouse Rock.”

The teachers had never heard of me. I said, “All I need is a mic and a piano.” I played at all kinds of [low and upper-income] schools in Manhattan. When I’d start with “Three is a Magic Number,” the kids would be nudging each other – they all recognized my voice.

It’s an age-old idea – the music gives [the lessons] a sort of vehicle. McCall summed it up saying that kids can’t memorize the [multiplication] tables, but they’ll sing along with rock and rollers and learn all the lyrics. It was a simple idea but it had never been exploited like we did it.

I was just reading about an economics professor who’s using hip-hop to teach economics to bored high school students. There are a lot of spinoffs and other songwriters are writing educational songs. Some of them come to me looking for approbation and approval, which I give them readily. It’s really spawned an interest in the connection between education and music, which is stimulating to the development of the brain.

Newall: Once, in the late 1980s – Tom Yohe, my partner who designed most of the series, was invited to Dartmouth. Their senior class does a theme every year that everybody works on, and their theme for that year of all things was “Schoolhouse Rock.”

So, Tom goes up to Dartmouth with a videocassette and does his little talk and slaps the cassette in. The film comes on the screen and every kid in the audience sings along with it. He said, ‘You won’t believe it – there are kids out there who know these damned songs!’ That’s been our experience ever since.

Bob was invited to do an event at the Kennedy Center, it was the 40 th anniversary of Schoolhouse Rock. I went with him and introduced him and participated in the show. We drew the largest crowd they ever had at the Millennium Stage; there were 2,000 people. And they sat there transfixed, singing along with Bob.

Afterwards, there was an autograph session. There were two individual Asian couples who came up to get our autographs and said, ‘Our kids never would have learned English without your films.’ That was just astonishing.

When we first did Schoolhouse Rock, Tom said to me, ‘These could be evergreens because every year, a new class of kids comes in and starts school and it could go on forever.’ Bob and I have been on a couple of NPR call-in shows and I really think it’s schoolteachers that have made it live. Eighty percent of the calls coming into these shows are from teachers talking about how they use it with their classes. For three semesters, I taught an advertising writing course at St. Johns University. My class looked like the U.N. – 30 percent of them were from the Caribbean and there were students from Asia. And they all knew about Schoolhouse Rock because they heard it when they were in school, they were introduced to it by schoolteachers.

Ahrens: Unlike theater, in television you never get an immediate sense of how your audience is responding. But over the years I’ve become extremely aware of how much people love Schoolhouse Rock. It shows in the letters people write, the many imitations and parodies you can find on YouTube, the TV shows that have used some of the pieces for political purposes. The little show we all took part in has become iconic on some level. It’s hard to find anyone who doesn’t know it and love it.

It never occurred to me that the little songs we had such a great time writing and producing would ever become as important as they seem to have become. Winning the Emmy certainly gave the series some weight and over the years people began to analyze its success and popularity. But we just kept writing and having fun. All the rest is gravy. My favorite part has been belonging to the Schoolhouse Rock family, and we’re still friends. In fact, just last night, George and I went to see Bobby perform at a night club in New York City. He was wonderful!

George, what led you to music initially and how have you been able to have a “second act” career as a jazz pianist?

I was drafted and was in the Army from 1953 to 1955. I always played jazz by ear and I wound up in an Army band in the 11 th Airborne Division, because I could play piano at the service club and the officers’ club on weekends. That was the start of my musical education.

While I was in the band, there was another guy who got his master’s in piano from Florida State. He said, ‘You’ve got to go to this school.’ I wound up going to Florida State and majoring in composition and theory. I had done big band arrangements when I was in the Army band, so in college I wrote some contemporary classical music that won some awards in the southeast. But to continue in serious music I’d have to commit to years more study. And economically that would have unfair to my first wife who had already worked for four years to help me get through college.

So, we moved to New York and I wound up working in the mailroom of an advertising agency for $50 a week. Since I had also done some writing in college, I went to the head of the agency’s copy department and said I wanted to be a copywriter. They had a client that needed radio commercials and he asked me to write some spots. At the end of the meeting the only commercials they bought were the ones I had written. So, suddenly I was a copywriter. They raised me to $75 a week. And that was the beginning of a different world.

During the summer on weekends, I used to play in a club called The Riptide on the Jersey shore. But when I got into advertising, I slowly began to play less and less. Except at Friday afternoon jam sessions called “Jazz at Noon. At those sessions, I got to play with the great Jo “Papa” Jones of Basie fame. And Mel Lewis, Thad Jones, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones, Sam Jones, Bobby Durham and lots of other big-name jazz players who were working in the city at the time. I even had the [opportunity] of playing opposite Oscar Peterson in one of those sessions!

Lynn, what led you to your current career in storytelling through musical theater?

One thing always leads to another, and a lot of what I learned [working] on Schoolhouse Rock I use today in writing musicals—a brevity of language, word pictures, a sense of entertainment, and so forth. Schoolhouse Rock taught me how to work in a studio, how to communicate with actors and musicians, and even how to record and mix. I also learned that music can dictate visuals, and in envisioning stage musicals, we are always thinking about what we’re seeing as well as what we’re hearing. I started writing for the theater as a way to stretch myself and try a new kind of writing. It has turned out to be my true career and calling, but Schoolhouse Rock certainly contributed to my skill set, abilities and confidence. It was a glorious and meaningful time in my life, and I’ll be forever grateful that my young self was given the opportunity.

Bob, what made you take a chance on a career in music?

I was in my high school band in Texas, playing clarinet. I had dabbled with a harmonica, a violin, and the piano around the house. I never thought of music as a real way of life. Just the idea of the ensemble… there are all these kids playing different instruments and playing different parts of the music and it fits together like an ensemble.

And so, right away it piqued me. I began to practice and really dig in and make it sound better for the whole band. After about two weeks in the high school band on the clarinet, I told my parents at suppertime, “I’m gonna be a musician.” My bandmaster was very talented and helpful, and he gave me clarinet and harmony lessons. So pretty soon I was already writing music in high school for the band to play. It was pretty bad, but I was doing it. And from that moment on, they didn’t resist me, my parents. So that was it for me.

And what inspires your songwriting?

I started writing songs that would fit my own personality and that I could sing with confidence and believe in. That sort of developed the writing and the singing. It took a good while but I worked on it for a number of years. I’ve played in a lot of little clubs in New York and Los Angeles, and later on in Europe. I was always looking for a new song – or learning old songs – and trying to sing them in a different way, in my way, seeking to communicate with the audience.

I used to work in a lot of bars, where they’re all talking and drinking and they don’t care much [about the music]. I was singing pop tunes like ones by Hoagy Carmichael that they might know, hoping they would stop for a minute and listen. That was my goal – to make them listen.

© MMXVII Joanie Harmon – From the forthcoming book, “Jazz on the Small Screen”

I could be wrong, but I think the caricature of Tom Yohe was drawn by my father, Jack Sidebotham, who also drew some of the cartoons.

LikeLike

Thank you for the sharp eyes, Jan – you are correct, my apologies for the error!

LikeLike

George Newall brought me in to write two songs for Schoolhouse Rock: Earth. I composed and sang “Save The Ocean” and co-wrote and sang “You Oughta Be Saving Water” with George and my old Rockapella bandmate Barry Carl. What a pleasure and honor to be part of this illustrious franchise!

LikeLike

What a GREAT read. I. Try to attend every performance of Bob Dorough’s at the DeerHead Inn and his upcoming 94th Birthday. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great Piece and well deserved !

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this piece. Well done!

LikeLike